How a DBMI Scientist and a Chicago Journalist

Teamed Up to Discover Dangerous Drug Interactions

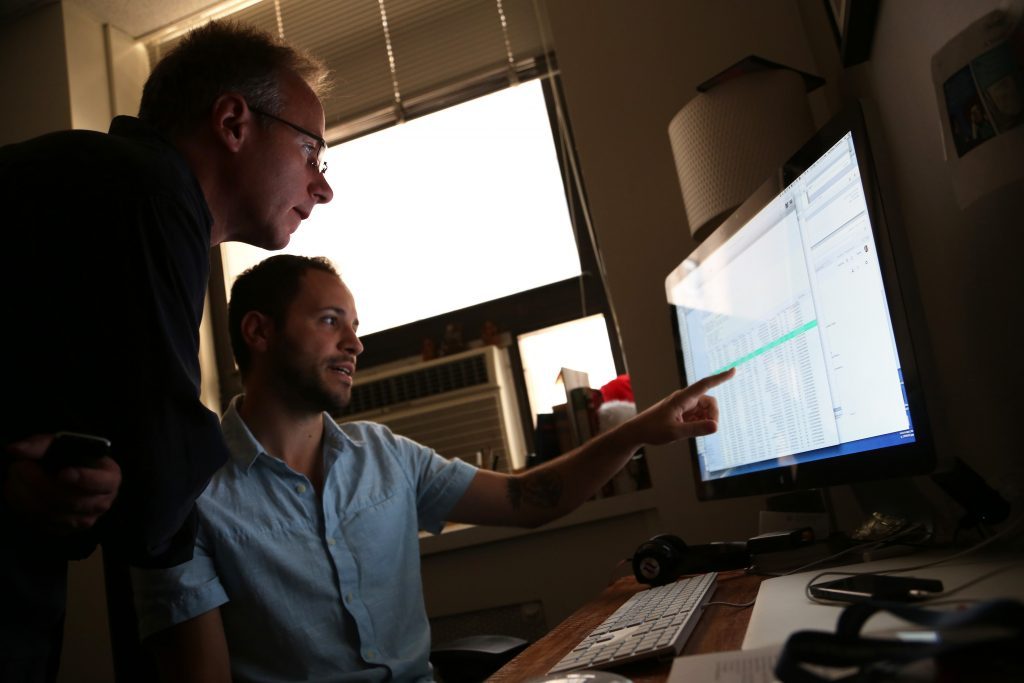

In February, Sam Roe and Karisa King published a front-page Chicago Tribune story investigating how big data could be used to discover deadly drug combinations. The article was a result of years of research and a unique collaboration between Roe, a Pulitzer-prize-winning reporter, and DBMI professor Nicholas Tatonetti.

The editorial process for the piece was unusual. Roe had been interested in dangerous drug interactions for years, but lacked the background and data resources to investigate the topic fully. He had tried searching the newspaper’s databases, but came up empty. After attending a talk in Chicago on big data by Stanford professor Russ Altman, Roe met with Altman, who told him that he should go out to Columbia and talk with DMBI’s Nicholas Tatonetti. Roe took the tip and booked his ticket to New York.

Having long believed a story on drug interactions was beyond his reach, Roe decided to pursue it after meeting with Tatonetti. “What really attracted me to Nick’s work is that he’s been a pioneer,” says Roe.

Tatonetti had been developing a method called latent signal detection, which infers the presence of hidden events by examining the effects of something after it happens. “It’s similar to how astronomers look for black holes,” says Roe. It also has all sorts of possibilities for finding drug combinations.

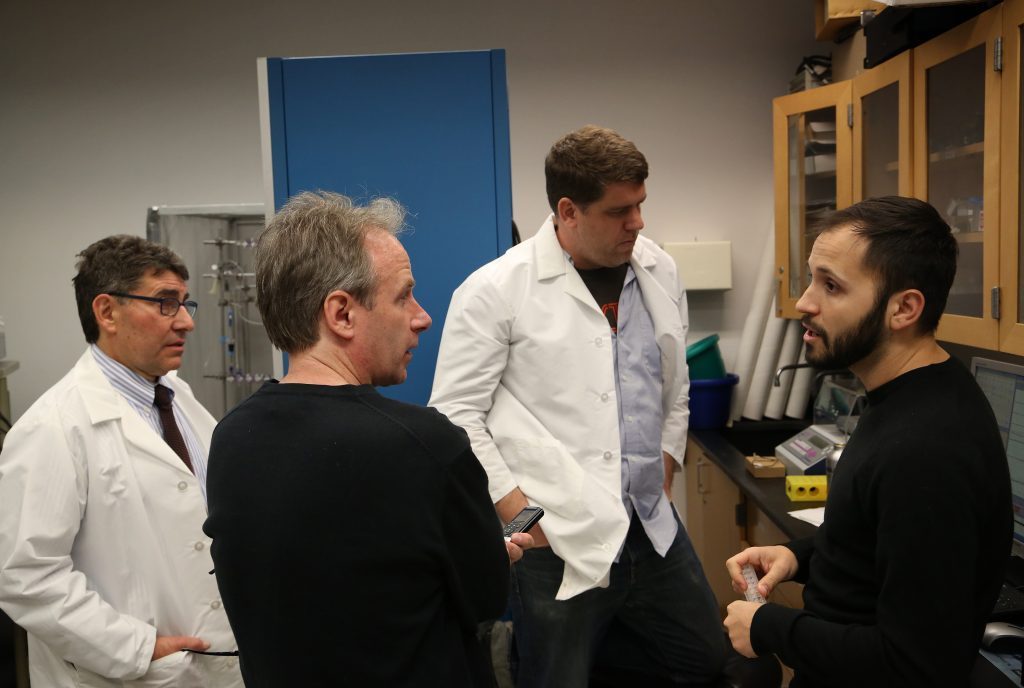

Meanwhile, Roe was interested in a particular type of drugs that impacted the QT interval – the time between heartbeats. Together with Raymond Woosley, an expert on such drugs, Tatonetti and Roe formed a team that worked together for more than two years.

As chronicled in the Tribune article, their unlikely collaboration ultimately identified four drug combinations that can potentially lead to a fatal arrhythmia. The team used Tatonetti’s methods to analyze a massive government database of drug complaints for signs of the heart condition. Then they combed through 380,000 electronic hospital patient files to confirm which drug pairs were indeed associated with an increased risk.

Tatonetti says the algorithms that drove these discoveries are based on the same logic that doctors use to diagnose patients. “When you are feeling ill and you say you have fever or pain or aching joints, the physician listening is building a mental model of what is going on in your body,” he explains. “That physician can’t see your disease but he can use little pieces of evidence in combination to come up with a diagnosis.” In short, the algorithm that led to Roe and Tatonetti’s breakthrough works by learning what an adverse event looks like based on effects it observes indirectly.

It’s not typical for a newspaper and a university to team up so closely, but Tatonetti believes citizen science is collaborative in its nature. “Nowadays there is so much data and so many techniques and so much expertise to bring into just one project that it’s foolish to try to do that yourself,” he says. “The days of lone scientists are over, and we need collaborations to move our research forward.” Collaboration, he adds, creates “a whole pipeline of discovery.”

Scientists and journalists dig for truth in different ways, which may have led to this project’s success. Journalists are trained to ask good questions, while scientists, says Tatonetti, “are trained to evaluate whether something is true or not.” “We can pursue questions with high impact in a systematic and thorough way and then present the evidence.”

Roe believes that journalists are uniquely trained at connecting with people to find answers. “At the end of the research, we can call the people who are accountable for these drugs and ask the difficult questions,” he says. For Roe, working with Tatonetti and Columbia University was a uniquely productive experience. “We have worked with scientists before, partnering with different scientific labs to do testing for us when we were looking at lead in toys and mercury in fish,” he says. “But this is different because we weren’t paying scientists for their time – the folks at Columbia were involved because they also wanted to find something.” He adds that a mutual passion shared with Tatonetti made this project one of his most exciting. “I remember one time we were walking out of his office, and Nick said: ‘Yeah, let’s change the world.’ That’s someone I want to work with.”

Together, the team is still working to uncover more hard-to-find drug interactions and continuing the experimental exploration of the interactions they found initially. There has already been one scientific paper published on the work, and another is due for release in the near future. “There’s a lot of talk out there, but here’s a really solid example of how big data can improve the average person’s life,” says Roe.