PhD Profile: Anna Ostropolets Uses Knowledge Engineering, Observational Research To Aid Those Who Need It Most

A clinician from Ukraine, Anna Ostropolets spent the first 2+ years of her dissertation research developing a data consult service, so that clinicians at New York Presbyterian Hospital could get new on-demand evidence at the bedside.

The COVID pandemic shut down her most efficient research methods — shadowing and speaking with clinicians — and ultimately changed the trajectory of her dissertation. It didn’t change her desire to create something that “could be used” by those who needed assistance the most.

Instead, Ostropolets pivoted to aiding the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in making one of its most important early vaccine decisions, publishing nearly 20 studies around the pandemic — including work on background incidence characterization that assisted the EMA — and impacting a variety of focuses within the biomedical informatics field.

Simply put, her efforts generated evidence that could be used by anybody in a time when information was most sought. Her mentor, George Hripcsak, marvels at that impact Ostropolets made throughout her time at DBMI.

“Anna has done an astounding job in innovation, productivity, publication, and real-world impact,” he said. “Her work has potentially helped hundreds of millions of persons, for example in developing the methods used in calculating clotting risk for the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in 2021. Anna pulled many research groups together to create the first world-wide inventory of medical terms; one outcome of that work was the PHOEBE tool for phenotyping, which is used by hundreds of researchers each year to generate clinical publications. Her data consult service showed the potential benefit and challenges associated with real-time and robust evidence generation at the bedside.

“Her thesis is well-placed in biomedical informatics, being driven by real problems and innovating in knowledge engineering in health,” Hripcsak added. “Researchers from around the world actively seek Anna’s collaboration in knowledge engineering and observational research, knowing her rigor and her productivity, and this reflects in her numerous publications. Collaborators are often surprised she is not already a tenured professor. It has been truly wonderful to work with her.”

Ostropolets, then in her early clinical days, found OHDSI before she began considering a PhD path. She started working on OHDSI vocabularies with Dmitry Dymshyts and found that she had a passion for the work, but not necessarily the background knowledge for it. Without a suitable place to train in her home country, she focused on one program — Columbia DBMI, the central coordinating center of OHDSI.

She connected with Hripcsak and Patrick Ryan, two OHDSI co-founders, and spent her early days working on the data consult service. Using Columbia EHR and claims data, she developed the service by shadowing clinicians during their rounds and collecting questions that would come up or needed answering.

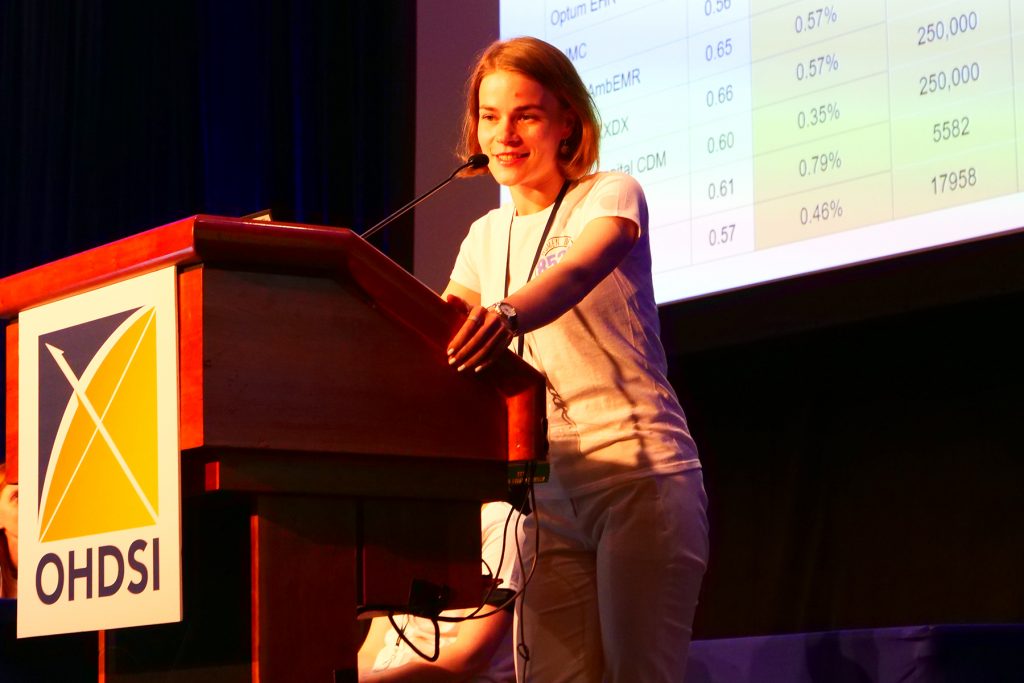

Anna Ostropolets demonstrates PHOEBE 2.0, an open-source tool for phenotyping, at the 2022 OHDSI global symposium.

“If a clinician saw a patient with a rare bacteria in the blood culture and didn’t know if this was serious, they could ask us if we saw patients like this at Columbia, and if so, what their outcomes were,” she explained. “Clinicians often believe they have enough information to make judgments, or they call for consults, but they can miss blind spots in their knowledge. They may not have enough evidence to choose the right treatment. To help them make informed decisions, you need to come to clinicians and talk to them, and identify these blind spots before they do.”

Ostropolets, who earned immediate credibility due to her own clinical background, had countless conversations with clinicians so that she could be prepared for the questions that might need immediate answers. When the COVID pandemic, the opportunity to shadow clinicians ended.

New opportunities, however, began just as quickly.

“A lot of people struggled with the change in environment, staying inside and pausing their research,” she said. “For me, it wasn’t a challenge because we started COVID work right away. The start of the pandemic was an exciting time for me because we had the study-a-thon. I sat here for two weeks working non-stop and being fully involved with OHDSI and different groups. It was so much fun.”

It was fun, but it was critical and timely work as well. Ostropolets was a lead or co-author on about 20 COVID-related publications, but her most significant impact may have come around characterizing incidence rates of adverse events across a network of observational databases, which directly contributed to the vaccine safety surveillance efforts of both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), including the EMA decision to reinstate the AstraZeneca vaccine in the setting of early clotting reports.

With the varying work around COVID and the inability to connect with clinicians as she had done prior to the pandemic, Ostropolets shifted her dissertation focus to a broad topic of reducing pre-analysis bias to generate reliable and responsive observational evidence.

“My focus was to develop something that will be used,” she said. “From this perspective, all of the pieces come together. The data consult service was something we wanted clinicians to use. Phoebe is something we believe researchers in OHDSI will use. OHDSI vocabularies are definitely something researchers are using. Our work with vaccine safety and effectiveness was something we knew the FDA wanted. All of the pieces are related in some way to bias in observational studies. More than that, they are coming from some of the real-world use cases that we saw.”

Ostropolets would be the first to note that none of this work can be done alone, a lesson she hopes future PhD students heed early in their research journey.

“I know a lot of people in various programs struggle with their PhD because it’s essentially five years when you are pretty much on your own,” she said. “You have an advisor, but you spend most of the time on your research. You are the primary person doing your research. It’s usually not a team. In OHDSI, at each point, there are always connections and teams. There are people who care about the same stuff you care about, whether it is the clinical side, or methods, or many other areas of observational science.”

They do more than care, however. They accomplish.

“One of the greatest advantages in OHDSI is that projects get done,” she said. “They get done fast. What you would typically spend one or two years on your own can be done much faster in OHDSI, and it will become a much better project because you have all of the collaborators with different experiences and perspectives. Usually, you collaborate with somebody smarter than you, and they contribute back. You want to join OHDSI because it will boost up your career, and your publishing record, but also of course because you become part of the warm and welcoming community.”

“One of the greatest advantages in OHDSI is that projects get done,” she said. “They get done fast. What you would typically spend one or two years on your own can be done much faster in OHDSI, and it will become a much better project because you have all of the collaborators with different experiences and perspectives. Usually, you collaborate with somebody smarter than you, and they contribute back. You want to join OHDSI because it will boost up your career, and your publishing record, but also of course because you become part of the warm and welcoming community.”

Ostropolets felt strong connections within the department, both from those deeply invested in OHDSI and those who focus their research elsewhere. The collaborative spirit is evident in both the publications and grants loaded with DBMI faculty and trainees, and it’s a spirit Ostropolets is hoping to maintain.

“I told George that if I’m staying in academia, I’m staying at DBMI, because it’s been so great,” she said. “If I go to industry, I still want to maintain my connections to DBMI. Leaving OHDSI is outside of my scope completely. Why would you? We have so many exciting projects to do. It’s a never-ending list.”